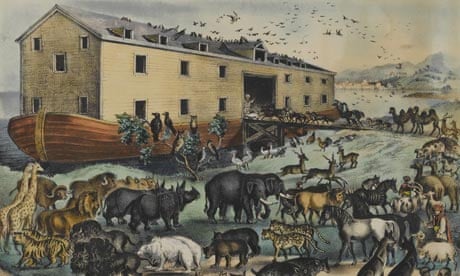

That they processed aboard the enormous floating wildlife collection two-by-two is well known. Less familiar, however, is the possibility that the animals Noah shepherded on to his ark then went round and round inside.

According to newly translated instructions inscribed in ancient Babylonian on a clay tablet telling the story of the ark, the vessel that saved one virtuous man, his family and the animals from god's watery wrath was not the pointy-prowed craft of popular imagination but rather a giant circular reed raft.

The now battered tablet, aged about 3,700 years, was found somewhere in the Middle East by Leonard Simmons, a largely self-educated Londoner who indulged his passion for history while serving in the RAF from 1945 to 1948.

The relic was passed to his son Douglas, who took it to one of the few people in the world who could read it as easily as the back of a cornflakes box; he gave it to Irving Finkel, a British Museum expert, who translated its 60 lines of neat cuneiform script.

There are dozens of ancient tablets that have been found which describe the flood story but Finkel says this one is the first to describe the vessel's shape.

"In all the images ever made people assumed the ark was, in effect, an ocean-going boat, with a pointed stem and stern for riding the waves – so that is how they portrayed it," said Finkel. "But the ark didn't have to go anywhere, it just had to float, and the instructions are for a type of craft which they knew very well. It's still sometimes used in Iran and Iraq today, a type of round coracle which they would have known exactly how to use to transport animals across a river or floods."

Finkel's research throws light on the familiar Mesopotamian story, which became the account in Genesis, in the Old Testament, of Noah and the ark that saved his menagerie from the waters which drowned every other living thing on earth.

In his translation, the god who has decided to spare one just man speaks to Atram-Hasis, a Sumerian king who lived before the flood and who is the Noah figure in earlier versions of the ark story. "Wall, wall! Reed wall, reed wall! Atram-Hasis, pay heed to my advice, that you may live forever! Destroy your house, build a boat; despise possessions And save life! Draw out the boat that you will built with a circular design; Let its length and breadth be the same."

The tablet goes on to command the use of plaited palm fibre, waterproofed with bitumen, before the construction of cabins for the people and wild animals.

It ends with the dramatic command of Atram-Hasis to the unfortunate boat builder whom he leaves behind to meet his fate, about sealing up the door once everyone else is safely inside: "When I shall have gone into the boat, Caulk the frame of the door!"

Fortunes were spent in the 19th century by biblical archaeology enthusiasts in hunts for evidence of Noah's flood. The Mesopotamian flood myth was incorporated into the great poetic epic Gilgamesh, and Finkel, curator of the recent British Museum exhibition on ancient Babylon, believes that it was during the Babylonian captivity that the exiled Jews learned the story, brought it home with them, and incorporated it into the Old Testament.

Despite its unique status, Simmons' tablet – which has been dated to around 1,700 BC and is only a few centuries younger than the oldest known account – was very nearly overlooked.

"When my dad eventually came home, he shipped a whole tea chest of this kind of stuff home – seals, tablets, bits of pottery," said Douglas. "He would have picked them up in bazaars, or when people knew he was interested in this sort of thing, they would have brought them to him and earned a few bob."

Simmons senior became a scenery worker at the BBC, but kept up his love of history, and was very disappointed when academics dismissed treasures of his as commonplace and worthless. His son took the tablet to a British Museum open day, where Finkel "took one look at it and nearly fell off his chair" with excitement.

"It is the most extraordinary thing," Simmons said of the tablet. "You hold it in your hand, and you instantly get a feeling that you are directly connected to a very ancient past – and it gives you a shiver down your spine."