In a bid to save lives and not overwhelm healthcare systems, countries have chosen different measures to confront Covid-19. At the height of Italy and Spain’s outbreaks, people could not leave their homes. In the UK, they can leave for an hour a day of exercise, and to get groceries. In the US, activity varies by state; in Nevada, the streets of Las Vegas are empty while in southern California, some beaches are full.

Even amidst the variation, Sweden stands out in its approach to Covid-19.

The country’s primary schools have remained open. Restaurants too, though congregating at the bar is discouraged and tables are set farther apart. Those who can are encouraged to work from home, but nightclubs can operate so long as the manager ensures that people keep an arm’s length from one another.

Sweden’s chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, who enjoys a sort of celebrity status in the country for his unflappable calm, says the strategy seems to be working: “We might have reached a peak and we are on the plateau,” he said at a briefing on April 15.

On April 26, deputy prime minister Isabella Lovin defended the strategy to the BBC: Sweden views Covid-19 as a “marathon, and not a sprint,” she said, and warned that citizens in countries with more extreme measures may tire of staying home.

The Swedes brokered a different deal than the rest of the world: Citizens take individual responsibility for social distancing, and the government keeps most of society functioning. There are some rules—high schools and universities are closed, gatherings of more than 50 people are banned, and people over 70 and those who feel ill are encouraged to stay home. But businesses largely remain open, and children who would otherwise need care are in school.

Citizens seems to be taking their responsibility seriously. Residents point out that they are practicing social distancing, with the elderly isolated, and families mostly staying home, apart from kids in school. Citymapper statistics indicate an almost 75% drop in mobility in Stockholm. Travel over the Easter weekend dropped more than 90%; the government did not tell ski resorts to close for Easter, a popular ski holiday time, but the resorts closed anyway. Lovin told the BBC it is a “myth that Sweden has not taken serious steps.”

But whether the strategy is working depends on which metrics you look at—and how you interpret them.

By the numbers

At the time of publication, Sweden had 18,640 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 2,194 deaths. That makes the country’s 217 deaths per 1 million people significantly higher than in neighboring Norway, Finland, and Denmark (whose populations are about half of Sweden’s), but lower than in Belgium, Italy, the UK, and the Netherlands.

In addition to a higher death rate (both in absolute and relative terms) compared to Denmark and Norway, Sweden has had high rates of infection and death in elderly homes, where more than half of the country’s Covid-19 deaths have occurred. In Norway, which has similar social safety nets, rates have been much lower.

While it represents a significant defeat for a country that prides itself on democratic socialism, Tegnell said the problem is due to weaknesses in the social safety net—not the coronavirus response. “It is not a failure for the overall strategy, but it is a failure to protect our elderly who live in care homes,” Tegnell said at the briefing on April 15.

But Sweden’s healthcare system has not been overburdened, a key goal of countries that have chosen lockdowns. Plenty of intensive-care beds are free, Tegnell said. The country more than doubled its ICU capacity to over 1,000 beds; currently 550 are occupied (link in Swedish). Meanwhile, there is no fraught debate over how to re-open society, and whether there will be a second wave, because society has largely remained open.

Sweden’s economy is still expected to be hit hard. According to Magdalena Andersson, the finance minister, GDP could shrink by 10% this year and unemployment could rise to 13.5%. Sweden is an export-led economy and thus dependent on a global economy that has effectively been shut down. Lovin, the deputy prime minister, said 90,000 people had filed for unemployment in the last four to five weeks. Claims in Norway are far higher, on a relative basis, suggesting there has been less of an economic hit in Sweden.

Perhaps the strongest indicator of success for the Swedish strategy will be the country’s ability to achieve herd immunity—the protection that emerges as a virus makes its way through a population. The more people who gain immunity to the virus, the fewer potential vectors exist to speed its spread. Patrick Vallance, the UK’s chief scientific officer, has said that about 60% of a population needs to be infected to build herd immunity.

But the idea of herd immunity is a contentious one. “[W]e don’t know how long that [immunity] will last and that should instill some doubt about that approach,” said Rowland Kao, a mathematical biologist who studies infectious disease dynamics at the University of Edinburgh. The Netherlands and UK initially followed a herd-immunity approach and quickly U-turned after projections showed that cases would soar and overwhelm the health system.

Tegnell insists herd immunity is not Sweden’s strategy. “Herd immunity is not a policy, it’s a status you can achieve,” Tegnell said. “We want as few people to get infected as possible, at a slow pace, so the health system can cope.”

Tegnell said in a briefing that the country’s policies in the pandemic were informed by science but also by the way Swedes have always valued independence. “It’s a long tradition that works very well,” said Tegnell. But not everyone is on board with the approach.

Not for everyone

On April 24, a group of 22 doctors, virologists, and researchers criticized Sweden’s public health agency in an op-ed published by Dagens Nyheter, the country’s leading business newspaper. “The approach must be changed radically and quickly,” the group wrote. “As the virus spreads, it is necessary to increase social distance. Close schools and restaurants. Everyone who works with the elderly must wear adequate protective equipment. Quarantine the whole family if one member is ill or tests positive. Elected representatives must intervene, there is no other choice.”

In late March, Cecilia Söderberg-Nauclér, a viral immunology researcher at the Karolinska Institute and one of the op-ed signatories, told the Guardian that the Swedish approach was “leading us to catastrophe.” A month later, she hasn’t changed her mind. “I see no indication that we are not heading for there in Stockholm,” she said in an interview with Quartz.

Söderberg-Nauclér said death rates appear to be higher that those cited by the Folkhälsomyndigheten (the Swedish health authority) of 0.1%. Between March 27 and April 3, the government randomly tested 773 people, finding an infection rate of 2.5% in Stockholm. Extrapolating from there, roughly 58,000 people would have been infected, which should have resulted in roughly 58 deaths three weeks later, but Stockholm just passed 1,022 deaths, suggesting a fatality rate closer to 1.7%, she said. She does not see the “plateau” that the authorities are citing and suggests ICUs could still be overwhelmed in a few weeks’ time.

Not enough is known, she said, to pursue a policy of allowing people to slowly get infected. “We should be humble that we know too little but we are going for a strategy that is untested in in the world, and there are too many unknowns that make this too risky,” she said. “I want to hold back and keep it under control and have faith in the medical community and understand the pathology,” she said.

There are various social and epidemiological reasons that, if Sweden’s strategy works, it might only apply within its borders. While comparisons to Denmark and Norway may be apt, comparisons to larger, more diverse countries are not. “What works for Sweden will not work for the UK,” said Kao. Sweden’s first case arrived later, too, so it had more time and information than other countries to begin social-distancing measures.

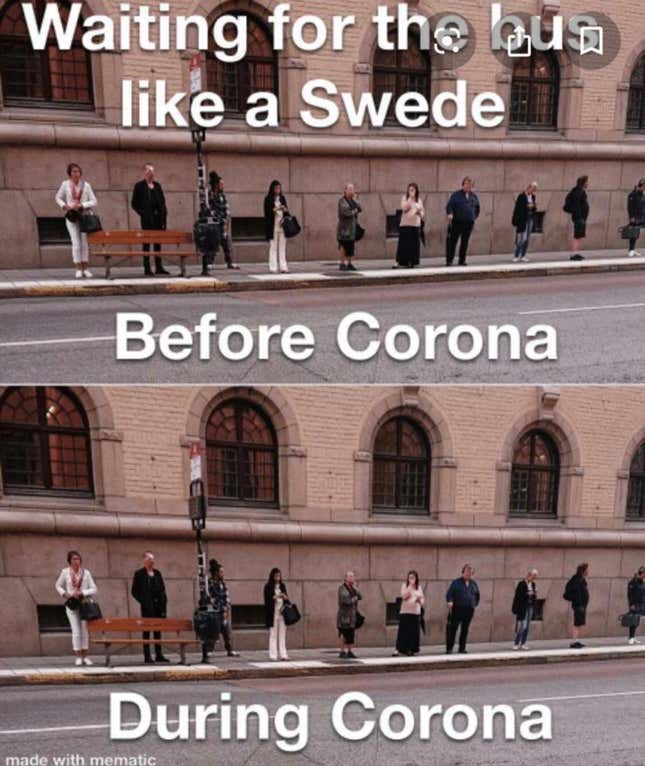

It may have an easier time executing them, too: Sweden has a small population of 10 million—about the size of Georgia or North Carolina—and that population is spread out. Over 50% of homes are single-dwelling households, which lowers the risk of transmission. Many people work from home and have fast internet access. Some have noted that Sweden’s character is well suited for social distancing. A popular meme is a before and after Covid picture of a bus stop, with people two meters apart in both frames.

There’s a cultural X-factor, too. Sweden’s strategy is notable for what it says about trust in the country: among citizens, and between citizens and their institutions. The government’s confidence in the citizenry underpins the policies established thus far, and it is trust in their institutions that, for now, leaves most Swedes supporting the current approach. But some no doubt share the dystopian feeling described by one Stockholm resident who told Quartz, “We are all part of a social experiment that we did not ask to be part of.”

What’s so different about Sweden

More than 80% of Sweden’s residents say they think their country’s approach is the right one. Life has changed, but kids can go to school, people can work, and businesses have not been uniformly shuttered.

Tegnell may have critics, but he is a calm, professional presence, who does not claim to have answers where there are none. During the April 15 briefing, he answered what he could, but to questions of immunity and knowing what was right, he repeatedly said “these are things we don’t know.”

“One of the real assets we have is calmness, a sense of normalcy, in this difficult situation,” said Lars Trägårdh, a professor of history and civil society studies at Ersta Sköndal University College in Stockholm. Tegnell, he said, “is an important part of that.”

Many Swedes also think the approach is logical in the context of the country’s history, culture, and values, which consider the “rights” of many, not just the elderly and sick, said Trägårdh. Children’s rights and gender rights are part of the calculus deciding what to close and keep open.

Tegnell echoed similar sentiments in his April 15 briefing. “When we talk about school closings we talk about the effects of children not being able to go to school and that’s important from a public health perspective,” he said, noting the importance of the first 10 years in life for long-term health outcomes. With schools closed, healthcare workers with children might not be able to work; grandparents, a high share of whom look after children, would be at risk.

“You don’t destroy the social fabric to save individuals, you have to pay attention and take care of society as much as you take care of individuals and people who are sick,” said Trägårdh.

He says Sweden’s social contract is based on a close alliance between the individual and the state, or what he calls “statist individualism.” Citizens have myriad protections provided by the state—unemployment, healthcare, good public schools, efficient government services—which allows them, in turn, to maximize their own choices (to live alone, to change jobs, to have children).

Trägårdh finds it amusing that libertarian groups in America are the ones cheering on Sweden now, since normally they would be the ones deriding Sweden’s “nanny state.” It is precisely because the government cares for and trusts it citizens, and because citizens trust the government, that Swedes are “free” to socially distance and keep each other safe.

Every leader faces tricky decisions in trying to navigate the balance of minimizing deaths with minimizing pain to the economy. Sweden has definitely opted for the path less traveled. The question is what difference it will make.

“Did Sweden try too hard to steer that middle course and crash on both?” asked Kao. “Only the inquiry after will tell us.”