1941 George Pell is born in the Victorian town of Ballarat to an Irish Catholic mother and a non-practising Anglican father. He is educated at Loreto Convent and St Patrick’s College in Ballarat.

1960 Pell begins studying for the priesthood at Corpus Christi College in Werribee.

1963 He continues studies at the Pontifical Urbaniana University in Rome.

1966 Pell is ordained by Cardinal Grégoire-Pierre Agagianian, an Armenian Catholic and the church’s leading figure on communism and the Soviet Union. Studies continue at Urbaniana University and then at Oxford, where he is awarded a doctorate of philosophy in church history.

1972 Pell returns to the Ballarat as a parish priest and, after only a couple of years, is appointed episcopal vicar for education.

Abuse is widespread in the diocese under Bishop Ronald Mulkearns. As the royal commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse later hears, Mulkearns moved paedophile priests from parish to parish as their abuse was discovered.

1973 Pell lives in the parish house of St Alipius in Ballarat East with the paedophile priest Gerald Ridsdale. Pell has always maintained he never knew Ridsdale was abusing children. But this is later disputed.

Ridsdale was a prolific sex offender who abused children throughout Victoria from the 1960s to the 1980s. What Pell may have known of Ridsdale’s offending and that of other paedophile priests becomes the subject of much of the royal commission’s later questioning.

1977 Pell is a member of the College of Consultors of the Ballarat Diocese, a group of senior priests who advise Mulkearns on the appointment of priests. In July 1977 Pell is part of a College of Consultors meeting that sends Ridsdale to his next parish, Edenhope.

Mulkearns knew about complaints against Ridsdale, but Pell later tells the royal commission Mulkearns deliberately withheld details from him and other consultors. “The suffering, of course, was real and I very much regret that, but I had no reason to turn my mind to the extent of the evils that Ridsdale had perpetrated,” Pell would later tell the commission.

September 1979 Pell is part of a meeting that discusses Ridsdale’s resignation from Edenhope and a meeting in January 1980 that approves sending the priest to the National Pastoral Institute in Elsternwick. Though Ridsdale is taken away from easy access to young children there, he continues to offend.

1981 Consultors meet without Pell to send Ridsdale to Mortlake, where he openly abuses boys.

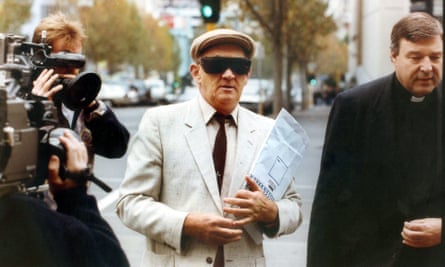

Photograph: The Age/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

1982 Pell sits on the College of Consultors meeting that decides to remove Ridsdale from Mortlake. The minutes of the meeting record only that “it had become necessary for Fr Gerald Ridsdale to move from the parish of Mortlake”.

1987 Pell becomes an auxiliary bishop of Melbourne.

1990 He becomes a member of the church’s powerful Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, a position he holds until 2000.

1993 Pell supports Ridsdale during his first court appearance for child sex offences. Ridsdale is convicted between 1993 and 2013 of abuse and indecent assault charges against 54 children. In 2017 Ridsdale pleads guilty to further charges of abusing 11 children.

1996 Pell is appointed archbishop of Melbourne. He introduces the Melbourne Response, which offers support and counselling to victims of sexual abuse but caps compensation payments. His move also prevents the church establishing the Towards Healing program, which is approved weeks later, as a nationally consistent protocol.

2001 Pell is appointed archbishop of Sydney, where he now oversees the Towards Healing program.

The commission later finds that during this period Pell and the Sydney archdiocese spent more than $1m fighting a legal claim by an abuse victim, John Ellis, to discourage others from attempting the same.Read David Marr’s analysis of the Ellis case here.

June 2002 Pell stands aside while he is investigated by the church over an accusation that he sexually abused a 12-year-old altar boy at a youth camp on Phillip Island in 1961 while a seminarian. Pell denies the allegations. The verdict of the retired judge is not proven but not dismissed.

2003 Pope John Paul II appoints Pell as one of 31 new cardinals.

2005 Pell takes part in conclave that selects Pope Benedict XVI.

2006 Pell leads Sydney’s successful bid to host 2008 World Youth Day.

November 2012 The Australian prime minister, Julia Gillard, announces the royal commission into institutional child sexual abuse, after a string of scandals including a submission to a Victorian inquiry from the state’s police commissioner, Ken Lay, that some of the church’s actions to hinder investigations – such as dissuading victims from reporting crimes to police – should be criminalised.

2013 Pell takes part in the conclave that elects Pope Francis.

2014 Pell is appointed the prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy, making him effectively the Vatican’s treasurer and widely reported to be the third most senior figure in the church hierarchy. He is said to be a possible future pope.

March 2014 Pell appears before the royal commission for the first time in Sydney. He is questioned about the treatment of Ellis and admits the litigation “was hard fought, perhaps too well fought by our legal representatives”. He says he should have exercised greater oversight over the case.

August 2014 Pell appears before the royal commission in Melbourne, where he likens the church’s responsibility for child abuse to that of a “trucking company” whose driver had sexually assaulted a hitch-hiker. He also says he took abuse claims from victims’ groups “with a grain of salt”, and defends the much-criticised 1996 Melbourne Response.

June 2015 The royal commission announces Pell is to appear before its second set of hearings into abuse in the Ballarat archdiocese. Pell indicates that he is prepared to come to Australia to give evidence.

December 2015 A week before Pell is due to give evidence, his lawyer makes an application for the cardinal to give evidence via videolink, citing health reasons. The application is refused but the appearance is postponed.

February 2016 Pell strongly denies allegations in the Melbourne newspaper the Herald Sun that he is being investigated for “multiple offences” while serving in senior positions within the church, saying they are without foundation and utterly false.

He calls for a public inquiry into the Victorian police, saying the allegations were leaked to damage him before his third appearance at the royal commission.

March 2016 The cardinal is cleared to give evidence to the royal commission via videolink after church doctors rule he is too ill to fly. Abuse survivors travel to Rome to hear his testimony. His decision not to return to Australia is widely criticised, including by the songwriter and comedian Tim Minchin, who labels Pell a coward.

Under questioning he continues to deny that he had any knowledge of the actions of Ridsdale when he was a priest in Ballarat in the 1970s. He says Ridsdale’s offending, once he did become aware of it, was a “sad story” but was “not of much interest” to him.

The conservative columnist Andrew Bolt says Pell was either “lying” or “curiously indifferent” to abuse around him, a criticism he later retracts.

Pell’s evidence concludes with him telling the commission he hopes his appearance will help victims heal. He describes giving evidence as “a hard slog, at least for me. I’m a bit tired.”

Read Melissa Davey’s coverage of Pell’s evidence here.

Read David Marr’s take on Pell’s evidence here.

July 2o16 The chief commissioner of Victoria police, Graham Ashton, confirms that allegations against Pell have been referred to the office of public prosecutions.

A Victorian man alleges he saw Pell expose himself to a group of young boys at a surf lifesaving club in the late 1980s.

October 2016 Australian detectives fly to Rome to interview Pell about child sexual abuse allegations. During the interview, Pell dismisses the allegations as “a load of absolute and disgraceful rubbish”. He tells detectives that if they lay charges against him it will damage the church.

February 2017 Detectives send an updated brief of evidence to the office of public prosecutions.

June 2017 Pell is charged with multiple sexual offences and is ordered to appear at Melbourne magistrates court on 26 July. Pell says he will fly back to Australia to clear his name.

July 2017 Pell makes a brief appearance before the magistrates court.

October 2017 Pell faces court for a second time and his committal hearing is set for March 2018. Committal hearings are held to determine if there is enough evidence to send a matter to trial.

January 2018 One of the key complainants against Pell dies. The complainant had alleged Pell touched his genitals repeatedly at Ballarat swimming pool in the 1970s, when the complainant was eight, while playing a game with children that involved throwing them into the air.

14 March 2018 After eight days of evidence in closed court to protect Pell’s accusers, the committal hearing is reopened to the public and the media. Pell’s barrister, Robert Richter QC, accuses a representative of the abuse research organisation Broken Rites of trying to “big-note himself” by going to police with allegations made to him about Pell.

15 March 2018 Richter accuses the father of an alleged victim of “inventing” allegations against Pell.

23 March 2018 The court hears allegations that Pell exposed himself to a choirboy while archbishop of Melbourne.

28 March 2018 Richter accuses the magistrate of bias towards prosecutors.

29 March 2018 The committal hearing comes to a close after four weeks.

1 May 2018 Magistrate Belinda Wallington delivers her decision, ordering Pell to stand trial over multiple sexual offence allegations, although many of the most serious allegations are dismissed. The details and nature of the charges may not be reported at this time. Pell tells the court he will plead not guilty when the case is heard before Victoria’s county court. The charges are to be split into two trials. The first, known as the “cathedral trial”, relates to allegations that Pell sexually abused two choirboys at St Patrick’s Cathedral in 1996 and 1997, while he was archbishop of Melbourne. The second batch of charges relate to allegations Pell molested boys at the Ballarat swimming pool in the 1970s, when he was a priest.

9 May 2018 The archdiocese of Sydney runs ads in the Catholic Weekly, seeking donations to fund Pell’s legal costs.

15 May 2018 Prosecutors request a comprehensive suppression order, later approved, which bars media reporting of the upcoming trials. The orders are common when an accused person is facing multiple trials, to avoid prejudicing jurors.

15 August 2018 The cathedral trial begins. It cannot be reported owing to the suppression order. A jury of 14 is selected from 250 people called to the court for jury duty.

13 September 2018 The judge, Peter Kidd, finishes his directions to the jurors after all the evidence has been heard.

19 September 2018 The foreman of the jury tells Kidd they cannot reach a unanimous verdict. Kidd directs them to keep trying.

20 September 2018 At 11am, with jurors making no progress, Kidd directs them to try for a majority verdict, which means a verdict of 11 to one. By the end of the day they have made no progress. A mistrial is declared.

7 November Jury empanelment begins for a retrial.

6 December 2018 The jury retires to deliberate. They are directed by Kidd not to make Pell a scapegoat for the failings of the Catholic church.

11 December 2018 The jury returns a unanimous verdict of guilty on all five charges after less than four days of deliberation. The suppression order means this can not be reported until the “swimmers trial”, set to be heard in April 2019, is complete. Pell’s defence lawyer says he will “absolutely” appeal against the verdict.

Pell is granted bail until 27 February 2019 in order to undergo knee reconstruction surgery in Sydney.

13 December 2018 Pope Francis removes Pell from his inner circle in a restructure of his Council of Cardinals. Pell still holds his treasury position, from which he stood aside to stand trial. Francis thanks Pell for his work on the council.

13 and 14 February 2019 Pre-trial hearings take place for the swimmers trial. Prosecutors push to be allowed to submit evidence that Pell had a “tendency” to molest boys in swimming pools, including from a man who says that when he was a child in Ballarat Pell touched him on the genitals while playing with him in a pool. But the man is unsure whether the touching was deliberate.

22 February 2019: Kidd finds the tendency evidence is inadmissible. It’s a significant blow to the prosecutor’s case.

26 February 2019: Prosecutors announce they have dropped the swimmers trial owing to a lack of evidence, and because one of Pell’s key accusers died in January 2018. As there is no longer a risk of prejudicing a jury, Kidd lifts the suppression order on the cathedral trial.

13 March 2019: Pell is sentenced to six years prison with a non-parole period of three years and eight months.

5 and 6 June 2019: Pell’s appeal is heard by the appellate division of the supreme court of Victoria.

21 August 2019: Pell’s appeal is dismissed by a majority of two to one.

17 September 2019: Lawyers for Pell lodge a special leave application with the high court.

12 March 2020: After a two-day hearing in Canberra the full bench of the high court reserves its decision about whether to grant special leave to appeal.

7 April 2020: The high court quashes Cardinal George Pell’s convictions, unanimously allowing his appeal. This is the conclusion of the legal process in Australia. There will be no further trials. Pell walks free after more than 400 days in prison.