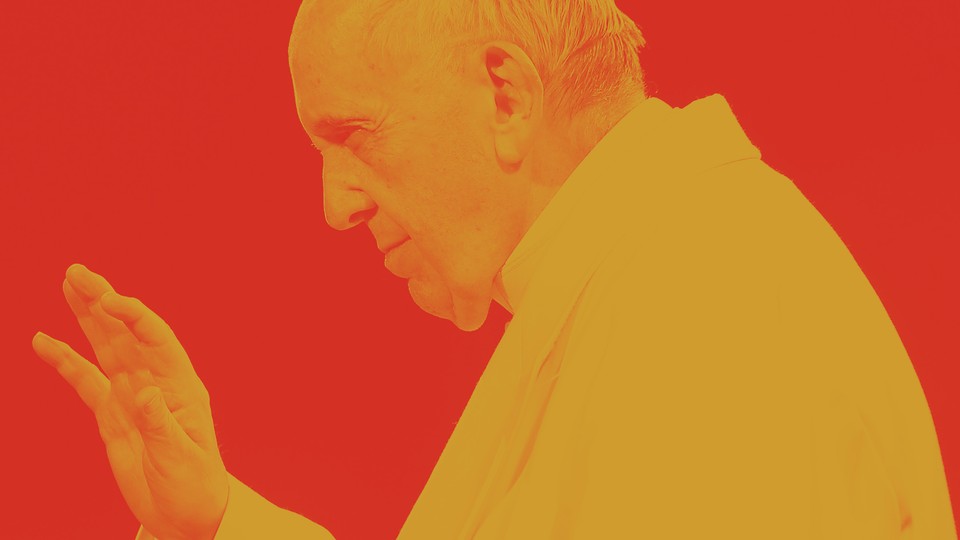

The Vatican’s Gamble With Beijing Is Costing China’s Catholics

In trying to hold the Church together, Pope Francis has compromised on religious freedom.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

Updated at 9:47 a.m. ET on May 14, 2024

No pope has ever set foot in China, but 10 years ago, Francis came the closest. On a flight to South Korea in August 2014, he became the first Vicar of Christ to enter Chinese airspace. Apparently that wasn’t enough. “Do I want to go to China?” Francis mused a few days later to those of us journalists accompanying him on his flight back to Rome. “Of course: Tomorrow!”

Francis has been more conciliatory to the People’s Republic than any of his predecessors. His approach has brought some stability to the Church in China, but it has also meant accepting restrictions on the religious freedom of Chinese Catholics and undermining the Vatican’s credibility as a champion of the oppressed. Francis sees himself as holding the Chinese Church together; he might be helping to stifle it in the process.

That trade-off becomes apparent when comparing the two major groups that make up China’s estimated 10 million Catholics. One is the state-controlled Church, overseen by the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, which has a long history of appointing bishops without the Vatican’s approval—a nightmare for popes because it presents the danger of a schism. In 2018, Francis mitigated that threat by negotiating an agreement in which the Chinese government and the Vatican cooperate on the appointment of bishops. The details of the pact, which is up for renewal in the fall, remain secret, but the pope has said it gives him final say. In return, the Vatican promised not to authorize any bishop that Beijing doesn’t support.

The agreement came at the expense of China’s second group of Catholics: the so-called underground Church, which previously ordained its own bishops with Rome’s approval and is now in effect being told by the Vatican to join the state-controlled Church. The underground community rejects President Xi Jinping’s campaign of “Sinicization,” a program that seeks to reinforce Chinese national identity, in part by demanding that all religious teaching and practice accord with the ideology of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Occasionally that means prohibiting religious worship entirely: Shortly before the Vatican and Beijing signed the deal, new legislation went into effect that led to stricter enforcement of such rules as a ban on minors attending Mass. And sometimes Sinicization means muddling Catholic doctrine with CCP dogma. As one priest in the official Church claimed in 2019, “The Ten Commandments and the core socialist values are the same.”

Whether the Chinese Church can remain authentically Catholic in the face of Sinicization is an open question. That Francis came to terms with the government just as the program intensified felt to some underground Catholics like a betrayal, a sign that he might tolerate the continued compromising of their faith. He accommodates Beijing in order to stabilize the Church in China, but Chinese authorities aren’t interested in the faith that Francis professes. They’ve made clear that they want a Church that submits to the state; such a Church might be stable, but would it be Catholic?

Safeguarding orthodox Catholicism in China depends on whether Francis and his successors can strike the right balance between cooperation and confrontation. The Vatican must cultivate greater influence in Beijing while also defending the faith—a daunting challenge for even the canniest diplomat.

The past six years make clear that the agreement on bishops has largely been a disappointment. Even some in the Vatican concede that it hasn’t lived up to expectations. “We would have liked to see more results,” Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s equivalent of a foreign minister, told America magazine in 2022. (The Vatican declined to comment for this article.) Only nine bishops have been consecrated under the agreement, and some 40 dioceses still have no leader. In the meantime, Beijing is happy to leave those dioceses under the administration of mere priests, Father Gianni Criveller, the editorial director of the Catholic publication AsiaNews, told me. Because bishops possess greater authority, they are harder for the government to control.

The agreement has yielded three new bishops in the past six months—the first new ones since 2021—but little else suggests much improvement in the relationship between the Vatican and China. Formal diplomatic relations remain a distant prospect, and China has rebuffed the Vatican’s proposal for a permanent representative office in Beijing, according to a Vatican official with knowledge of the talks, who described them on the condition of anonymity. The latest “Five-Year Plan for the Sinicization of Catholicism in China,” adopted by the government-controlled Church in December, makes no reference to the Vatican or the pope.

Still, the Vatican achieved its primary goal of reducing the risk of schism. “The aim is the unity of the Church,” said Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican secretary of state, defending the agreement in 2020. “All the bishops in China are in communion with the pope. There are no more illegitimate bishops.” Unity, in this case, means integrating China’s underground clergy into Beijing’s state-recognized hierarchy. In other words, Chinese Catholicism will be more and more controlled by the government, an undesirable outcome for Francis but one that he’s apparently willing to bear.

Some see that calculation as prudent. Francesco Sisci, a Sinologist and an expert on Vatican-China relations, told me that if the Vatican continued cooperating with the underground Church and holding the CCP at a distance, “you have to wait for the current power to fall, and who knows if the new power will be better than the old? In my opinion, the choice to go underground is much riskier.” As Richard Madsen, a professor emeritus of sociology at UC San Diego, put it to me, the agreement on bishops “gives a certain stability to the Church … so that in the long run it can develop and flourish.”

But Catholicism in China certainly doesn’t seem to be flourishing now. As Fenggang Yang, a sociology professor at Purdue University, told me, the Vatican’s conciliatory approach has demoralized Chinese Catholics. The agreement has put greater pressure on the underground churches to join the official Church, he noted, reducing their freedom to evangelize. The Vatican knew this was coming. In 2023, Archbishop Gallagher said that the deal “was always going to be used by the Chinese party to bring greater pressure on the Catholic community, particularly on the so-called underground Church.” Still, he defended the agreement, calling it “what was possible at the time.” Not all Chinese Christians are having such difficulty; Yang said that the decentralized evangelical Protestant “house churches” have continued to grow despite repression.

History suggests that resistance rather than compromise makes for a vital Church. During the Cold War, the Vatican pursued a policy of accommodation with Communist states in the Soviet bloc, negotiating over the appointment of bishops. But it was in Poland—where the Catholic hierarchy was least cooperative with the authorities, and where an underground Church was strongest—that Catholicism remained most vibrant.

Unlike Poland, China has only a small Catholic minority. But even there, the more uncompromising and persecuted portion of the faithful—the underground Church—has the higher morale, Criveller told me. “Those in the official Church are theoretically freer because they do not have to worship in secret, but in fact all their initiatives must be approved and agreed on with the officials in charge of religious affairs,” he said. “They are more easily discouraged.” Criveller noted that many Catholics in the state-controlled Church lose respect for bishops and clergy who are seen as “too aligned with government policy.” Ceding ground to Beijing might limit oppression, but it can weaken the authority of the Church.

The pope’s willingness to negotiate the 2018 agreement reflects two central features of his pontificate: his multipolar view of the world and his preference for dialogue over confrontation. Francis often flouts the geopolitical consensus of the West, questioning its authority and sympathizing with its adversaries—suggesting, for example, that NATO may have provoked the war in Ukraine by “barking at Russia’s gate.” China’s increasing power, which has so alarmed the West, is for Francis all the more reason to engage the country. While calling for the religious freedom of Christians in China and elsewhere, he also seeks closer ties with the governments that persecute them.

These tendencies have become more pronounced since the deal. The Vatican has grown both more conciliatory toward the state-controlled Church and less supportive of the underground Church. In 2019, the Vatican publicly encouraged underground clergy to comply with the CCP’s demand to register with civil authorities, even though they would be required to sign a statement endorsing the “independence, autonomy and self-administration” of the Church in China. At least 10 underground bishops have refused, according to the Vatican official; one was arrested earlier this year.

In another sign of acquiescence, Rome begrudgingly accepted the decision by Chinese authorities to transfer a bishop to its Shanghai diocese last year without consulting the pope. The bishop, Joseph Shen Bin, is the head of the Chinese bishops’ conference, which the Vatican doesn’t recognize, and an avid proponent of Sinicization. As he recently told an interviewer, “We must adhere to patriotism and love for the Church, uphold the principle of independence and self-management of the Church … and persist in the direction of Sinicization of Catholicism in China. This is the bottom line, no one can violate it, and it is also a high-voltage line, no one should touch it.”

Vatican officials have suggested that Sinicization is akin to the Catholic Church’s long-standing practice of inculturation—that is, presenting the Church’s teachings and practices in the terms of different cultures. But Yang, the Purdue professor, makes a crucial distinction: The goal of Sinicization, he argued in Christianity Today, “is not cultural assimilation but political domestication—to ensure submission to the Chinese Communist party-state.”

Shen Bin is forthright about this. In another recent interview, he stressed that Sinicization means not only adapting liturgy and sacred art to traditional Chinese culture, but also interpreting Catholic teaching in accordance with Communist doctrine. Sinicization, he said, “should use the core socialist values as guidance to provide a creative interpretation of theological classics and religious doctrines that aligns with the requirements of contemporary China’s development and progress, as well as with China’s splendid traditional culture.” Shen Bin is scheduled to speak next week at an academic conference at the Vatican, alongside the Vatican secretary of state. By accepting the dominance of the official Church, whose bishops Shen Bin leads, Rome is in practice accepting the supremacy of politics over religion.

Another cost of Francis’s overtures has come in the form of his silence about China’s human-rights violations. In July 2020, amid China’s crackdown on prodemocracy protests in Hong Kong, Francis decided not to deliver prepared remarks calling for “nonviolence, and respect for the dignity and rights of all” in the city, and voicing hope that “social life, and especially religious life, may be expressed in full and true freedom.” Vatican diplomats privately expressed puzzlement at the pope’s decision.

Francis has drawn particular criticism for his failure to denounce China’s treatment of its Uyghur Muslim minority, whom Beijing has forced into reeducation camps to eradicate their religion and culture—a striking omission given the pope’s emphasis on promoting dialogue with Islam. The most he’s said on the matter came in a book published in 2020, in which he made a brief reference to “the poor Uighurs,” including them in a list of “persecuted peoples.”

The Vatican’s reluctance to denounce China has also caused tension in its dealings with the United States. In September 2020, then–Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seemed to criticize Pope Francis’s relative silence while speaking to an audience in Rome that included the Vatican’s foreign minister. After noting the Vatican’s unique ability to help protect religious freedom in China, he admonished: “Earthly considerations shouldn’t discourage principled stances based on eternal truths.” Sisci, the Sinologist, told me that Pompeo’s comments only helped Francis in his dealing with the Chinese authorities, reassuring them that the pope was not “an instrument of U.S. policy.”

For now, the agreement on bishops is temporary, requiring renewal every two years. This raises the question of what Francis’s successor might do. The next pope likely won’t have his hands tied; he will be free to join the West in taking a more confrontational—or, as Pompeo would have it, principled—tack with China.

Alternatively, he can wait and see if Francis’s approach bears fruit. There’s an old saying that applies to the Church and China in equal measure: They think in centuries. The wait could be a while.